Light & Land

Michael Kenna interview: “Curiosity is important.”

18th April 2019

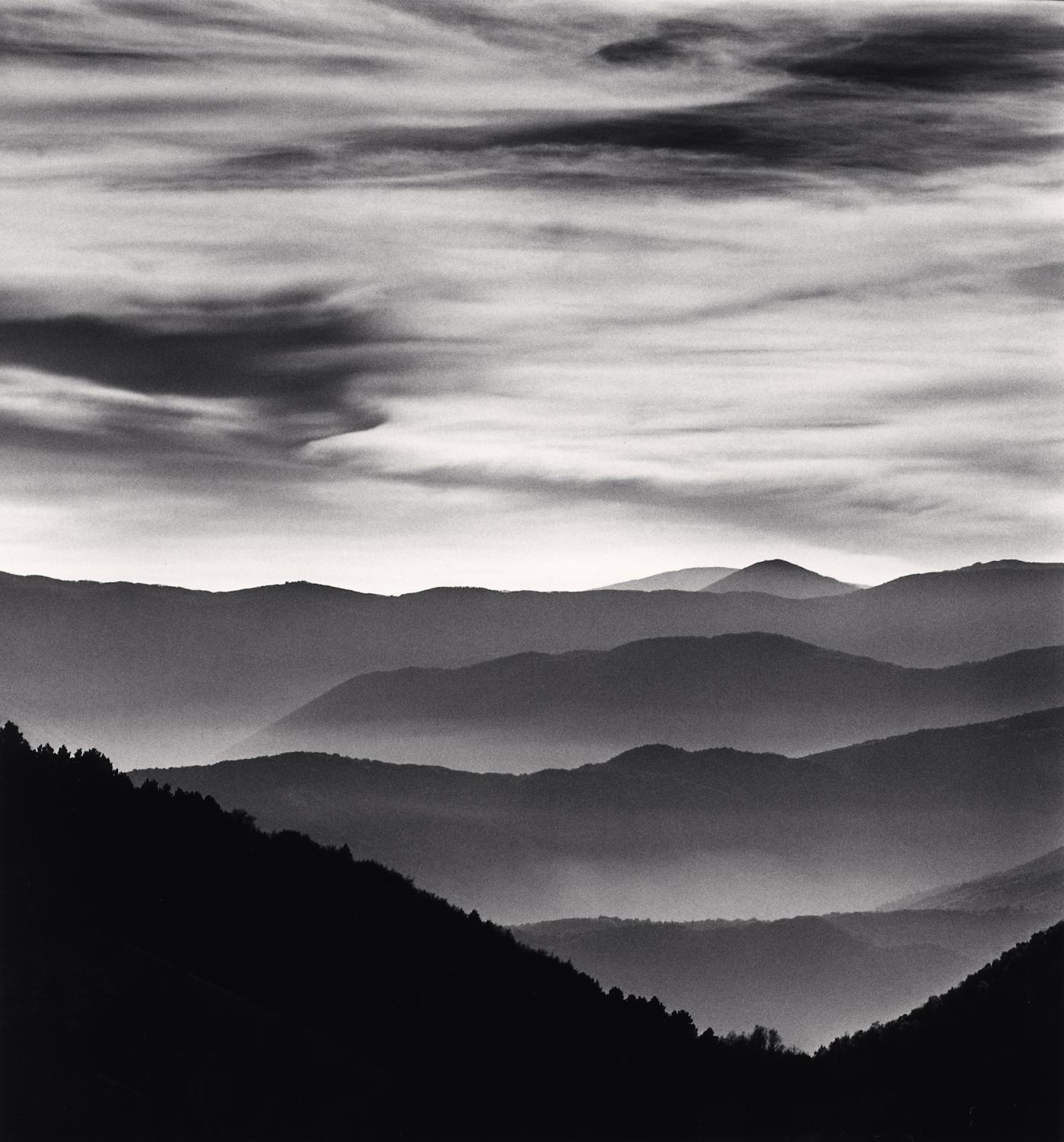

“I’ve often said that I could happily be a photographer with no film in my camera,” says landscape photographer Michael Kenna. A wandering spirit, Kenna's spent 40 years travelling the world, exploring wild, natural locations, from Europe to Asia, as well as industrial zones, abandoned buildings and religious shrines. Thankfully, he does always take his cameras with him. While much of the world has gone digital, Kenna, originally from England, still works with traditional Hasselblad film cameras, producing black and white photos in his signature minimalist style, often experimenting with long exposures of more than 10 hours. Recent adventures, though, have seen him experimenting on the side with Holga ‘toy cameras’.

Here, he talks to Graeme Green about capturing the spirit of a place, long exposures, long-distance running, toy cameras and his love affair with France…

How do you go about capturing the ‘spirit’ of a place, rather than just the look of a landscape?

I try not to make specific, conscious decisions ahead of time about what I’m looking for. I find locations, usually by walking. I look for some sort of resonance, connection or spark.

For me, approaching subject matter to photograph is a bit like meeting a person and beginning a conversation. How do I know ahead of time where that will lead? Curiosity is important. So is a willingness to be patient, to allow a subject matter to reveal itself.

Do you imagine or ‘see’ a picture in your mind before you start working on a photograph?

I don’t like to approach a subject with a pre-conceived finished print in my head. It’s the opposite of people like Ansel Adams. I never feel I’m the paparazzi making an exact copy of what’s out there. I always feel it’s a two-way street. You’re giving something to the landscape and it’s giving something to you.

We have infinite options of how to photograph something. That extends into the darkroom afterwards. That’s one of the reasons I haven’t gone over to digital. I prefer the slowness, the unpredictability, the complications. You never know what you have. It’s like the excitement of opening up a Christmas package when you get your negatives back.

Are the results often surprising?

There have been many occasions when interesting images have appeared from what I had considered uninteresting places. The reverse has been equally true. I fully accept that I do not have the answers. I am certainly not in control, and I like that.

How does working in black and white, rather than colour, change what you look for?

Having less information allows your imagination to work more to create more options. I like this idea. It goes back to writing. With haiku poetry, just a few words suggest an enormous world, rather than a big encyclopaedia that holds lots of information.

I try to eliminate elements that are insignificant, unimportant, distracting, annoying. I concentrate on elements that suggest something. I prefer an element of suggestion in my photography, rather than a detailed and accurate description. I think of my photographs as visual haiku poems, rather than full-length novels.

You sometimes use exposures of 10 hours or more. What do you do with all that time?

Time is a luxury. It’s a luxury not to have to do something, just to stand, to watch, to experience, and not to always have a full agenda and a busy schedule. It allows you to wander off in your mind.

One of my other pastimes is long-distance running. It’s a similar sort of thing. It’s a physical activity, but once you get past the two- or three-hour mark of running, it’s almost like an out-of-body experience. It seems you can solve all the world’s problems. It’s completely illusory, of course.

Most people think of photography as capturing a moment. What is it that you like about long exposures?

Yes, my work is ‘the decisive 12 hours’, not ‘the decisive moment’. Often, it’s not the pictures I’ve taken that I considered to have the perfect light and exposure that are most interesting. I like the ones where there’s something beyond my control. We photographers tend to be a bit controlling, and I’m always trying to liberate myself from that.

Your new book, Holga, contains photos taken with the low-tech, ‘toy camera’. What’s the appeal of a Holga?

I work with Hasselblads most of the time. They’re heavy, cumbersome. You have to spend a lot of time thinking about what you’re doing. The Holga is really very whimsical, instant, unpredictable piece of equipment. You can carry it in your pocket.

I have four or five of them. Each one has a different characteristic. They’re not machine-built to the point they’re consistent, so you really don’t know what you’re getting ahead of time.

Is the Holga proof that expensive gear isn’t vital to good photography?

Absolutely. I’ve always believed that. It’s like a pencil. You can use it to do an incredible drawing or write some amazing verse, or be an accountant. There’s so much you can do with one piece of lead in a pencil. It’s the same with a camera.

Do you find it useful to explore new approaches to photography?

Yes. If you use the analogy of food, you might know exactly what you like, exactly what restaurant you’re going to go to and exactly what you’re going to order. The question is, do you continue with that because, “Yes, I know I like it”, or do you experiment and say “There’s this taste I’ve never tried before and maybe I should try it”, in the understanding that you might not like the taste or it’ll be a failure?

I think most of us look to be constantly creative and constantly curious about what else there is. As you advance, you see yourself repeating patterns and past successes. You have to constantly force yourself away from those patterns.

Which are some of your favourite countries to work in?

I’m at a point in my life where I love to photograph in many of the places I’ve photographed in the past. I use the analogy of a friendship. It’s nice to deepen and renew and reacquaint with that person, instead of constantly meeting new people. There’s something very good about having deeper relationships with countries too.

I find I’m returning more to China, France, Italy, Japan, places where I’ve been before. I could keep going to places like those for my whole life and still be content. I just did two projects in Italy, a book on Abruzzo and one on confession boxes. I could spend my life in Italy or France.

What keeps drawing you back to France?

France has so much to offer. I’ve photographed there more than in any other country. Brought up in England, I came out of a European tradition. My first photographic masters were Eugene Atget, Bill Brandt, Mario Giacomelli and Josef Sudek, among others. They are all romantics at heart, concerned with photographing a feeling.

Eugene Atget, for example, inspired me to photograph the Le Notre Gardens in and around Paris. His dedication to photographing Paris all his life taught me that nothing is ever the same; the same subject matter can be photographed in many different ways and in different conditions.

With digital cameras and smartphones, most people now travel with a camera. What do you make of the ubiquity of photography?

I choose to opt out. Everyone nowadays is a photographer because everyone has a camera on their phone. That’s just the way it is. It’s not something I’m against.

Most people are content just to take instant photographs and put them out into the world very quickly and easily. There are always going to be some who take the time and delve deeper. It’s a bit like using Garageband on the computer. You can make music very quickly, but to really master an instrument takes years.

_

Holga by Michael Kenna is published by Prestel. See www.prestel.com for details.

Confessionali: Reggio Emilia (Corsiero Editore ) and Abruzzo (Nazraeli Press) are also available now.

For more on Michael Kenna's photography and his books, see www.michaelkenna.net.

Michael Kenna portrait by Song Xiangyang.

All other photos by Michael Kenna, in descending order: Distant Mountains, Passo delle Capannelle, Pizzoli, Abruzzo, Italy (from the book Abruzzo); Trabocco Punta Aderci, Study 2, Vasto, Abruzzo, Italy (from the book Abruzzo); Holga cameras; White bird flying, Paris, France (from the book Holga); Confessional, Study 6, Chiesa di Sant'Andrea, Gualtieri, Reggio Emilia, Italy (from the book Confessionali). Photos in the mini gallery are mainly from Holga, with some also from Abruzzo, Confessionali and miscellaneous works.