Light & Land

Waterland: Visual Storytelling and the Illusion of Progress by Ed Rumble

18th October 2022

‘[O]nly animals live entirely in the Here and Now. Only nature knows neither memory nor history. Man… is the story-telling animal. Wherever he goes he wants to leave behind not a chaotic wake, not an empty space, but the comforting marker-buoys and trail-signs of stories.

Graham Swift, ‘Waterland’ 1983

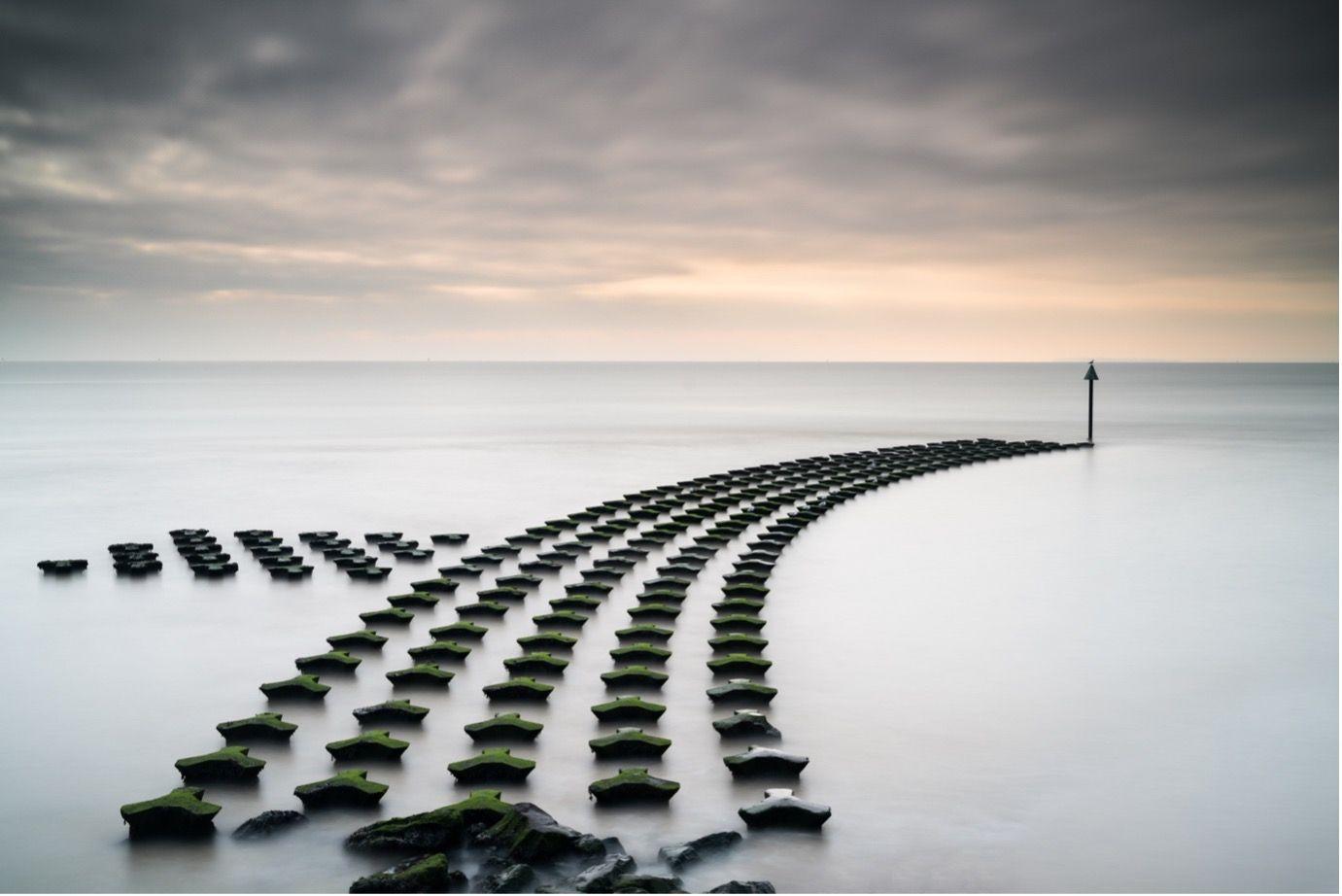

Our tour to the East Anglian coast will reveal a region that is constantly shape shifting. There are no towering Cornish granite monoliths, Pembrokeshire shales or Sussex chalk cliffs to beat back the sea and prevent its encroachment. In East Anglia there are no fixed borders between the sea and the great shingle banks, marram topped dunes and meandering estuaries. The landscape is in constant motion as it is moulded, formed and reformed by a conversation between water and land. The hand of man is ever present too and equally fluid in shaping the environment that we will be exploring. Fishermen’s Huts, and paraphernalia, at various stages of life between the new, weathered, and decrepit, lie amongst the boats that are launched, sailed, beached, and forgotten, to be reclaimed by the estuary silt. Piers and jetties are thrust forward, retreat into disrepair, and are washed away by the currents. Sizewell A still stands as an empty brutalist icon of technological progress while all the while its cooling platforms are rusting away in the North Sea.

Thus, in Graham Swift's novel, ‘Waterland’ which is the Fens close to our own explorations, time is not linear but cyclical. Progress is not discerned by some ever constant forward momentum towards enlightenment. Like the tides and the water cycle, History ebbs, flows, forms and reforms the present with reference to a collection of repeating motifs, events, decisions, mistakes and relationships. If one needed proof, History as a subject is littered with references that validate the circuitous nature of time: revolution, restoration, reformation, Rise and Fall… just like the tides and the rivers that flow into the sea only to be scooped up and returned again to the land. Despite the modern world’s obsession with growth, novelty and ambition, ‘Progress’ towards a futuristic nirvana is as elusive and illusory as the futile attempt to control the water, reclaim the land and bend nature to our will. The tides inevitably will confound our efforts, turn pasture back into salt marsh, silt up the river estuaries and erode the sea defences. In Swift’s novel the ungraspable future is built on East Anglian mud that slips through our fingers. It is the antithesis to the Neoclassical view of nature as divine order and the Victorian view of nature as something we can harness and strip mine to facilitate progress.

For Swift, even the ‘Here and Now’ is a confusing, disconcerting place. To make sense of it we construct historical narratives and stories that offer familiar patterns and pathways that explain who we are and how we got here: history repeats. Thus Swift’s protagonist Tom Crick is both a History teacher and a product of His-Story. The same might be said of the Suffolk fishermen with their tales of the sea and their ancestors, landing mystical catches and surviving storms a century ago. Our creation of historical narrative bridges the time and knowledge gap between the past and the present and is what distinguishes us as human beings both physically and metaphysically.

As photographers, our cameras will allow us to tell the stories of the landscape and the people that work and shape it. We may try to order our understanding of the region in the construction of photographs that form a narrative of the lowlands of Suffolk. Telling stories with our cameras is an endeavour of which perhaps Swift might approve. For it achieves two noble aims. Firstly, photography is driven by curiosity which is a crucial life force of huge significance and value.

“Nothing is worse… than when curiosity stops… It weds us to the world. It is part of our perverse, madcap love for this impossible planet we inhabit. People die when curiosity goes”. (p.155)

Secondly and inherent in its nature, photography is a form of abstraction. Even photographs that are not manipulated with long exposures or in Photoshop are abstracted from reality due to the selection of subject, perspective and in the difference in the way the camera sensor renders the world versus the human eye. This abstraction from the complexity of the world is a form of meditation that allows us to momentarily escape from the bleak news cycle or the pressures of life.

Our photographs achieve the same aims as Swift’s stories: the construction of our photographs help

us cope with the fear of meaninglessness, chaos and disorder in the ‘Here and Now’.

"It's all a struggle to make things not seem meaningless. It's all a fight against fear…” (p.182)

We are obsessed with progress, even in photography where we frame it as the never-ending quest for megapixels, resolution and sharpness. Should those be the ultimate standards by which we judge our images? If one were to pixel peep at the works of the great Suffolk landscape painters Thomas Gainsborough and John Constable would they be diminished by the discovery that we can see their brushstrokes on the canvass? No, we return to their greatest works again and again, just as we will retrace some of their footsteps across the region during our tour. We reference them in our own photographs consciously and subconsciously: the subjects, form, composition, colours and lighting: these are the motifs that repeat and echo down the ages in Waterland and elsewhere as we try to interpret and reveal the world to our audience through the narrative in our own pictures.

Surely this return is more valid than embarking on a quest for technically perfect yet soulless or jarring compositions. Or images where, in the name of progress, the hand of the photographer is all too visible in extreme ultra-wide perspectives, razor front to back sharpness or the pumping of saturation to alienating, disconcerting proportions. They might as well be pictures of the surface of Mars; they offer no solace in forming our own recognisable narrative of life. In Suffolk we shall revel in our own visual storytelling and hopefully create images that we can return to again and again to source joy, peace and escapism.

Ed Rumble, Oct 2022.